Immersion is a musical. When I wrote it I heard the songs in my head as well as the incidental music. Because it was written as a series I was able to to create chapters individually along with my musical compositions that accompanied them.

But what I really wanted to create was a fully interactive online experience (remember this was all conceptualised at the start of COVID 19). I have spent a good few years working and experimenting with different media and a cost-appropriate means of designing the book. I remained committed, despite the end of lockdowns, to the idea of an inspiring interactive book which worked with the storylines and allowed the viewer to totally immerse themselves in the experience of the story and its storytelling techniques.

I have finally satisfied all my prerequisites and am ready to release a series of books this year. I launch in April with the Book of Immersion Volume 1.

Watch this space please!

$20,090

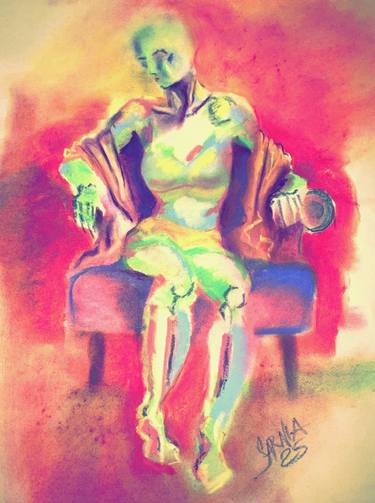

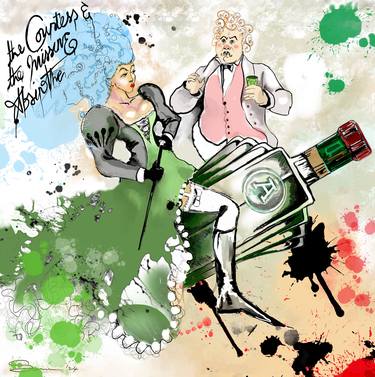

Painting, 33 W x 27 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $120

sold

$1,590

Painting, 22 W x 33 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

Painting, 21 W x 33 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

$1,280

Digital, 20 W x 33 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

Digital, 19 W x 27 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

Painting, 30 W x 40 H x 2 D in

Prints from $100

Digital, 10 W x 14 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

Digital, 16 W x 23 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

$1,010

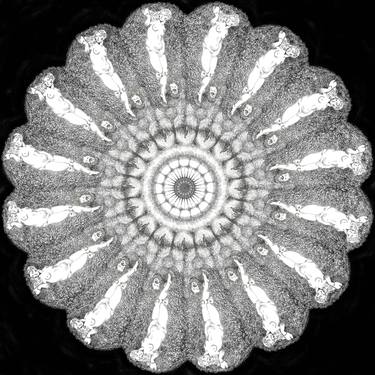

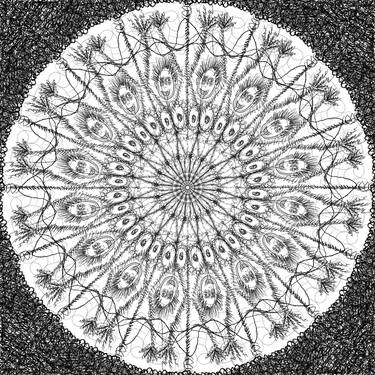

Digital, 36 W x 36 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

$10,090

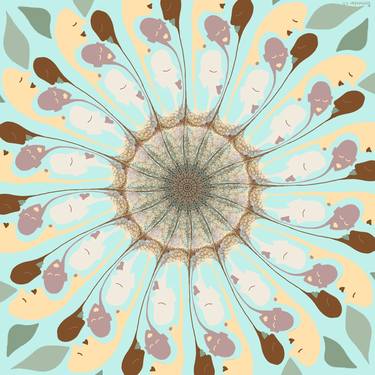

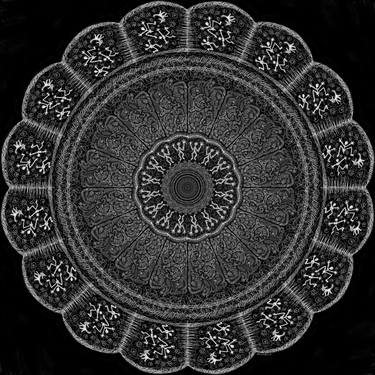

Digital, 25 W x 25 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $40

$8,090

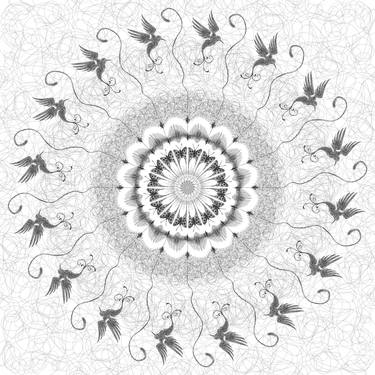

Digital, 25 W x 25 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

$1,590

Digital, 25 W x 25 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $40

$10,090

Digital, 25 W x 25 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

$10,130

Digital, 25 W x 25 H x 0.1 D in

$10,090

Digital, 25 W x 25 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

sold

$1,090

Digital, 25 W x 25 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

sold

$10,080

Digital, 41 W x 17 H x 0.1 D in

Digital, 12 W x 12 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

Digital, 12 W x 12 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

Photography, 12 W x 30 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

Photography, 282 W x 171 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

$1,610

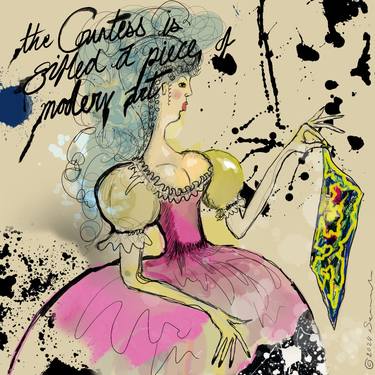

Digital, 36 W x 36 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

$1,310

Digital, 36 W x 36 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

$1,310

Digital, 36 W x 36 H x 0.1 D in

Prints from $100

#artbysarnia #saatchart #books #immersion #bookofimmersion #sarniadelamare

#interactivebooks #musical #taletellerclub